Automatic transcription:

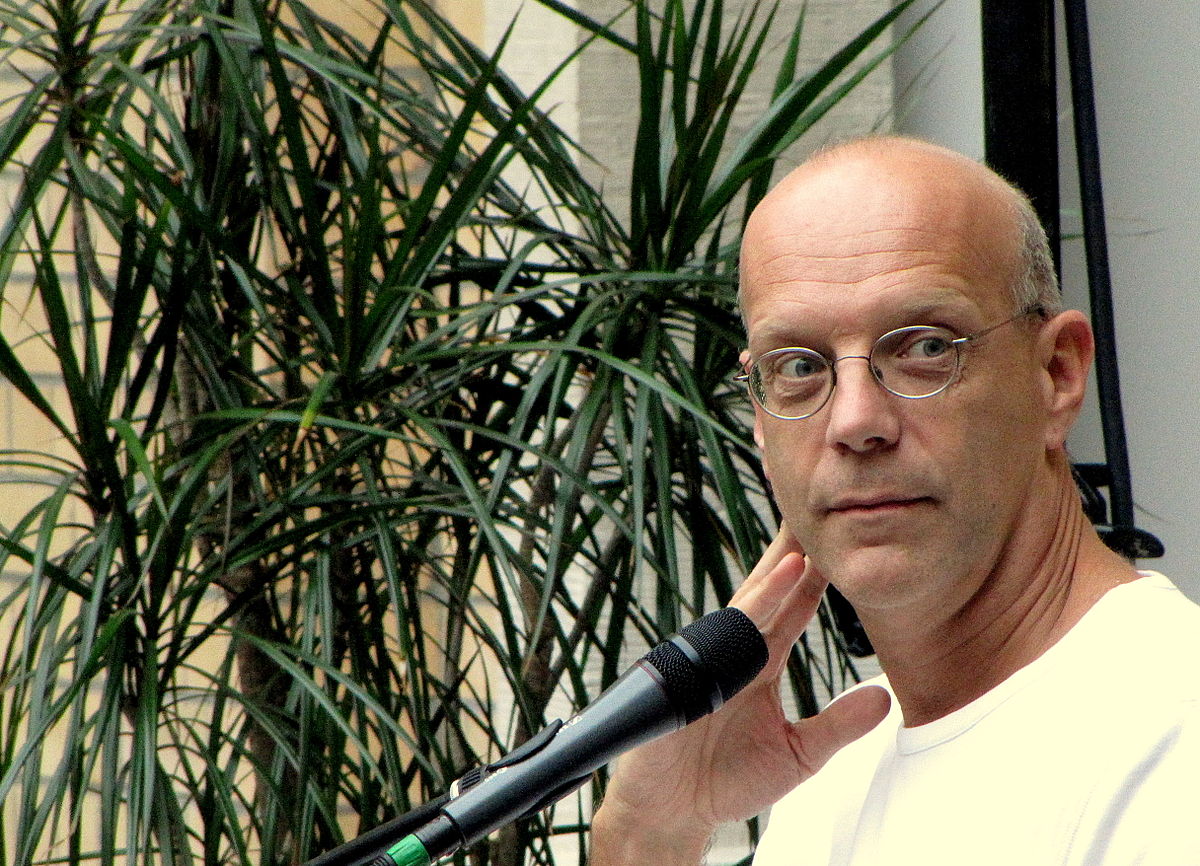

Alessandro Oppo: Welcome to another episode of Democracy Innovators podcast. Our guest today is Geert Lovink. Thank you for your time.

Geert Lovink: Thank you.

Alessandro Oppo: I have questions regarding the internet. You have wide experience with internet and networks. The internet is quite a new experience for human beings. How would you describe what the internet actually is, what the internet should be in your opinion, and eventually how we can reach that situation in which the internet is again a place of hope for all people interested in creating a better world?

Geert Lovink: The internet term has a military background. It is definitely a product of the Cold War, in that sense it is born out of the rubble of World War II. It is the creation of cybernetic principles and early computer science. The internet itself is an early network that was invented in the fifties and sixties and started working in 1969. It is based on the early principles of time sharing between computers that were remotely in different locations. So it is really a computer network.

People sometimes forget that, because these days of course the internet is mostly accessed on smartphones, but it is basically a network between computers. Later on in the seventies and eighties, by accessing these computer networks through terminals using computer language, initially Unix computer language, people started to see that they could not just only communicate to another computer but that they were actually, through chat and email etc., communicating with other people that were in different locations. So they were not just accessing a computer to tell it what to do or computation, but they were actually talking to other people elsewhere.

This was initially inside the United States, then in the eighties also between United States and its allies in India, Australia, and of course in Europe. In the nineties, this network starts to become more privatized. It was no longer a network that was only accessible to the military and later on academia, but in the early nineties, ordinary people like me were getting access to it.

In the beginning, in 1990, the internet was competing with other computer networks. There were bulletin board systems, but then there was also America Online, CompuServe, and a lot of others. But gradually in the 1990s, the internet started to become the dominant computer network. This is also because it was quite cheap and kind of public. It was a public computer network because it came from academia after all.

Then of course because of the invention by Tim Berners-Lee, the World Wide Web was created in 1991, which meant that it started to have a very easy-to-access interface. People who did not have computer programming skills were able to start using it, and the first websites came. The rest is history, as they say. It grew very fast because of venture capital that was added to it, leading to the first dot-com boom and then of course in 2001 also the first dot-com crash and recession. We have seen hyper growth ever since that period around 2000. There were about a billion people then, and now we are over four billion people using it worldwide.

Alessandro Oppo: When did the internet get your attention? I mean, were you excited when you discovered the internet, the World Wide Web? Is there any episode, any particular moment that you remember?

Geert Lovink: Of course, there is the epic Galactic Hacker Party in the hippy temple in Amsterdam called Paradiso. We organized a hacker conference there in August 1989, quite an exciting time because at the time also the Berlin Wall and changes in Eastern Europe were about to happen. Of course, these things are related because the big changes in '89-'92 were not only about geopolitics but also coincided with technology and globalization.

These things opened up the possibility for many people worldwide to start to communicate with each other and exchange materials in ways that were almost impossible and very slow and expensive before. There were possibilities to democratize the media landscape, and this was the initial promise. I came from the new social movements, from squatting, from the anti-nuclear movement, and we had a lot of experience with building our own alternative media using free radio, pirate television, and of course a lot of publishing of books, magazines, and so on.

In all these media, we already made use of computers. In the 1980s, it was already possible to create music, to do desktop publishing, and maybe a little bit more in the nineties we started to create digital videos. All these alternative underground experiences were directly tied to the democratization of all the tools that made it much easier not only to produce but especially also to distribute and exchange materials. Then later of course, we were not only exchanging materials but we were communicating with each other.

Alessandro Oppo: The access to culture is very important, and I would like to ask you about your background, eventually also starting from when you were a child if you have something to say about the memories that inspired you, or of course your academic background and professional one.

Geert Lovink: What's defining is maybe not so much my early experience with computers, which of course go back to the 1960s when all this was also very much related to science fiction. I grew up with that kind of imaginary. I started using punch cards in computers probably for the first time in the early 1970s in school, and came across these machines that for us were primarily used to make calculations. I liked that, I liked the idea that we're ultimately still talking about very clever interfaces to machines that ultimately just make an enormous amount of calculations for us. That's a computer, that's a smartphone - these are calculating devices.

I am also, inevitably, a child of 1984, which is not of course the year but the title of the famous George Orwell book. I grew up with a very high awareness of the surveillance state and the idea of the computer that was going to be used by the state and by big corporations to surveil us. This was an idea that probably came up already in the 1970s, when Western police apparatus and states were using computers to control the population.

I come from the Italian autonomist and German autonomist school, in which this kind of use of the computer was theorized very early on. So the computer was never really an innocent device. From the very beginning, we knew about its military origins and its evil intentions.

I want to take out one specific book, which is German but very influenced by Italian autonomist thinking from the 1977 movement. This book is written by two Germans, and it describes the way the Nazis were already using the IBM computers, the very early ones which were maybe not so much computers but calculating and sorting devices. This story really deeply influenced me when I read it in West Berlin when I was living there in the squats, about the way the Nazis were using the IBM computers in their relentless effort to kill all European Jews in the Holocaust.

So the computer always played an important role in sorting the population, sorting out, selecting people. The computer as a selecting device has always stayed with me. So when we started to enter this field of the democratization of the computer, we were always doing this with mixed feelings. We knew of its very destructive nature and capabilities, and knowing also that we had to intervene there but not doing that with too much naivety or utopian ideas.

We were very well aware from the mid-eighties onwards that the fight over the architecture of the computer and computer networks was going to be a very tough one and was going to define the decades to come. This was clear very early on.

Alessandro Oppo: About your professional experience, some academic background... Would like to share something? How did it happen?

Geert Lovink: I studied political science and sociology from 1977 till '84, but this was of course also very much defined by my involvement and participation in a range of new social movements, particularly the squatter movement in Amsterdam but also in Berlin where I lived. In my life, I've always gone back and forth between Amsterdam and West Berlin, which was later of course called Berlin after the fall of the wall.

Initially, this was very much about political philosophy and theory and sociology. Of course, at the time, the study of Marxism, the history of the labor movement, socialism, but in my case anarchism was really defining my own intellectual trajectory. We tried early on to really develop that in contrast with our own experience in the social movements, knowing that the big stories of the twentieth century around Marxism and the emancipatory power of the working class was going to an end. We then literally experienced that of course in the collapse of the Soviet Union five or ten years later.

We actively contributed to the decline of this Stalinism and rigid dogmatic forms of Marxism. Because of my involvement in the whole question of media communication, I developed an interest in what was happening in West Germany at the time, which was called the rise of media theory. I kind of developed myself also as an independent media theorist. That sounds a little bit strange because I was an academic - I never really saw myself as an academic. I saw myself more as an organic intellectual of the social movements and as a media theorist. That's basically what I'm still practicing and trying to develop further.

This field in my personal biography is very much related to two Germans who knew each other quite well from the city of Freiburg in the south. One is called Klaus Theweleit, and he is the author of "Male Fantasies," a book that really defined me, maybe together with Deleuze-Guattari but also with Elias Canetti's "Crowd and Power." A lot of things in this epic work kind of come together.

The other one that also was there at the time is Friedrich Kittler. He is a media theorist, and he has written a number of books that really defined my intellectual biography. You could call him the Foucault of the media. He really kind of completely revolutionized the initial groundwork that Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan laid, which is the earlier Canadian media theories from the postwar period.

I started to participate in this scene, in this German media theory which was quite large at the time in the late eighties and early nineties. What then happened is that I kind of took this experience of the hackers and the computer networks and media theory and brought that to the context of the emerging internet in the early and mid-nineties.

Alessandro Oppo: You have a lot of experience with internet, and as you reminded us, the internet was created for military purposes. Unfortunately, it seems that humans, when we develop new technology, we use it to kill each other, which is sad. But eventually the internet can be, as you said, used to democratize access to culture. I'm thinking about how internet challenged the way knowledge was produced and distributed, also thinking about copyright. Something also very awkward because of AI - if I read something and then I write a book, who is the owner of that content? These are philosophical questions, but maybe as a society we have to rethink how knowledge is distributed, and if it's convenient. I honestly think it's not convenient for society to have this kind of economic barrier to access culture. I'm referring also to the Foundation for the Advancement of Illegal Knowledge.

Geert Lovink: Let me first start with that because that's such a great episode and very important part of my life, especially in the eighties and nineties. I joined the Foundation for the Advancement of Illegal Knowledge in 1983 as a small group of Dutch floating intellectuals. We were all unemployed, we were not academics, we operated outside on the fringes of the social movements, and our aim was to develop an independent media theory, really focused on the question of how this speculative field that was opening up could be defined, could be designed with subversive and independent concepts.

We were really like a classic Deleuzian concept machine, if you like, outside of academia. It also meant that what we wrote, we also practiced. We had our own radio stations and publishing houses, and we were also giving classes and reading groups and so on. And yes, we were also writing books, and this was happening the whole time in the eighties and nineties in Dutch. We did not write in English.

This is definitely before the internet in that sense. I myself started to write in English only when I was 35 years old, when it just became impossible to translate everything. So initially I wrote only in Dutch and in German, and then because of the troubles of translation, this was just not viable anymore, so I switched to English, a language that I knew since I was a very small kid.

It was not a question that we were not good enough in English or something like that, but we enjoyed writing in our own language, which I think in the eighties and nineties was definitely much more widespread. These days, unfortunately, it's different. Why are we not talking in Italian? This is really a mystery to me why we are having this conversation in English, but it's something about our times and also about the way in which the production of theory and collective intelligence has shaped Europe in the past two decades.

The group produced a number of interesting books. We wrote the history of the Amsterdam squatter movement - it's called "Cracking the Movement" in English. But maybe in this context, the most relevant is the book that came out in '92 in Dutch and then in German and many other languages, and eventually also in English in '98, called "The Media Archive." It is really a book with an enormous amount of speculative figures and concepts. Most famous is probably the data dandy, which is kind of a person related to the early days of surfing the web. But also the idea of sovereign media was very important.

Sovereign media were basically media that were only broadcasting to themselves and had emancipated themselves from any idea of an audience. That I'm now talking to you - I'm not talking to other people, right? We are just having fun ourselves with the medium that we are using, and in this case our medium is the internet.

So for us, sovereign media was a very important emancipatory moment because broadcasting and distribution can also be very cumbersome and boring. If you look at how TikTok and Instagram are producing an enormous amount of influencers and how boring they are, you can see that broadcasting or webcasting is quite a burden on humankind. We should really get rid of that idea because it's really not leading us anywhere. It's just very boring content that comes out of this. To get rid of the idea of reaching other people, this kind of evangelical impulse inside us, is something that we thought we should make fun of.

Alessandro Oppo: It's a good question, the one that you made about why we are not speaking in Italian. I know that you also speak Italian. And I also agree about the quality of content on social media. About that, I think about the, let's say, independence of thought. I mean, we are having a discussion, then the discussion is going to be published, and an algorithm that we do not control in any way is going to distribute the content based on the traffic.

Geert Lovink: Even access is an idealistic notion because maybe in secret we hope that the algorithm will visit us, but maybe that's not even going to be the case. So in that sense, the whole thing is also based on a very idealistic notion that all content will be utilized in one form or another. I fear that it's going to be much more bleak, and that only a very selected group of content makers and people who are in control over the databases will eventually define what knowledge for humankind is.

It's very clear for me that very soon we will have a kind of shadow cyberspace outside of the AI machines where people will still kind of trade other types of content, because AI will really be so boring and will shut itself down necessarily for a range of reasons. So it will not include the thoughts of you and me, I can tell you.

Alessandro Oppo: This is also a fact connected with why we are speaking English. I mean, at the moment the most famous social networks came from other countries, mainly the US, and there is some sort of political influence because of that.

Geert Lovink: We have to understand that this is already an incredible limitation in a way. When we look at it from the incredible diversity and depth of cultural knowledge worldwide - we don't even have to talk about indigenous knowledge, but we can also just talk about our own - there are so many layers that will not be opened, that will not be covered, that will be excluded and forgotten if we do not act and if we do not actively organize counter-databases, counter-knowledge, counter-libraries of written and performed human experiences that are very rich.

In fact, the archives of the twentieth century are incredible, and I really fear that most of that will just be forgotten, not just because it's not digitized. The idea that we are going to save our souls only through digitization is only partially true. I think there's anyway an enormous richness of cultural memory that cannot and will not be digitized, and that is anyway embodied knowledge already stored inside us, not just in our brains but in our entire bodies - you and me and millions of others.

So we have to really be careful in the coming years not to reduce all this in the whole AI spectacle that is ahead of us. But I'm confident that many of us will see that this only represents a very poor one percent of all the things that we've gathered and have access to.

Alessandro Oppo: I'm optimistic about the trend that the system that in an unnamed turn of quantities will go toward an internet of quality.

Geert Lovink: You asked me before about the history of content, and for me that is a really fascinating topic that we don't really hear much about. In computer science but also in Silicon Valley, people have very ambivalent ideas about content. According to Marshall McLuhan already, content didn't really matter. The really hardcore materialist media theory already tells us that content really doesn't matter. It's not what it's about, but it's about the way the computer networks are organized, how they are, what its architecture looks like, what it excludes and so on. But the content itself is irrelevant.

In the 1980s, when I was really becoming fully aware of this, that was quite a shock because in the sixties and seventies we were still thinking in terms of ideology and in terms of hegemony - when you have good ideas and you bring them and share them among the people. These were all still movements that were driven by the idea that if you have good content and if you can tell the truth, you can convince people and you can make a difference. The revolution will ultimately be driven by this kind of rational motive that eventually the truth will set us free.

The realization that this might not really be the case, or not the case anymore (maybe in the past it would have been the case, who knows), but certainly in today's world, content is just garbage basically. For me that was very difficult because I've always struggled with this idea. On the one hand, I have to fully be aware of it and have to understand it and reconcile that with it. On the other hand, I am a content maker myself. I'm a writer and we're producing books and videos and so many weird and good and subversive content.

This is a very deep paradox in our approach because our materialist theories tell us a very different idea, while our passion and our creative energy and theory and political debates and everything - all that is essentially garbage content. This is very difficult, and up to today this is true even more so with AI.

AI is a very expensive and complex set of rules and theories and languages, but it can just use the whole history of humankind in a couple of weeks to train itself. There you can already see that the content that it's using to train itself is basically garbage - can be anything. That's pretty shocking again and again, to think that artists will not make a living, writers, any kind of creative worker will have to be either supported by the state or just basically have an everyday job, do something else, and then create these beautiful things - write a symphony, a novel, film, etc. - in the evening hours, because with the content you will not be able to make a living.

This slow realization of the past twenty or thirty years has been really difficult for all of us, because if you are really like us on top of the game in the internet, this is the ultimate realization - that those who create good content are basically the garbage workers.

Alessandro Oppo: I like the paradox between producing content and at the same time recognizing the limit of that content. I'm thinking about the Institute of Network Cultures, a wonderful project. I'm also thinking about networks - network could be also network of people, network of devices, network of devices and people. How can we rethink centralization and decentralization - information is power and vice versa. Now there are new ways maybe for humanity to relate to governance. What is democracy for you? Can these new technologies help to transform the system that we are calling democracy, I mean liberal Western democracies?

Geert Lovink: From a media theory and from an internet perspective, having worked in these fields for the last thirty years, I have to say that the internet and democracy have very little in common. They don't really touch, or if they touch, it's pretty disastrous.

We can talk about the democratization, the opening up of the medium itself. That is in itself an interesting one, and of course I have been working on that for all this time - to educate people, to show how to work on open access and open source free software, creating libraries, making alternative content available, etc. This is the use of computer networks in education - you name it. So this is the democratization of the medium itself.

Now, the relation between Western parliamentary democracy and the internet is a difficult one from quite early on. There is no real link. Let's start with one very obvious obstacle: from very early on, the computer networks have maybe contributed to the creation of discourse, of talking, maybe also of discussion or of debate. There are a lot of hidden power plays there and inequalities, but you could say the internet is kind of a discursive machine.

However, is that feeding into the decision-making process that is happening in parliament or in government? Maybe not. Very problematic to even point at where this is really contributing in a constructive way.

Nowadays of course we know that with the internet you can bring down governments and subvert all sorts of systems. The alt-right is very good at it. So for the last ten years, we have really studied at length how internet culture and social media in particular can be used to undermine the state, the rule of law, or parliamentary rules, or corrupt government apparatuses or political parties - you name it.

But most of all what we see there is that the internet has had no influence whatsoever on something like voting. It's very interesting - internet is not a tool and has so far not been a tool for decision-making processes. You could say okay, maybe the internet is used in election machines, but if you have a closer look and if you look at the long history of how hackers look at the design and the way the internet can be used in the elections, you will see that most of the computer hackers will say: don't use any internet if you want to organize an election.

This is very strange. Already since the 1990s, when you go to hacker conferences etc., the strong advice is: don't use any computer networks in the elections, because they can and will be hacked, and the whole democratic process will inevitably be undermined by machines. That in itself is interesting. So computer networks and democratic processes of collective decision-making - they don't go together, they don't match, and that in itself is very interesting. This is a takeaway of many generations of computer hackers, and I fully agree that we should not let these two things even come close to each other.

Alessandro Oppo: This is very interesting because I actually think we have some technological solutions that could actually help people to agree about certain topics, but at the same time it's very true that the technology can be hacked in some way, and then the result may be compromised by a bug.

Geert Lovink: I've been very interested in decision-making processes and using software in small groups and maybe even in smaller social movements, but even there the outcome was a mixed feeling. The fact that the outcome can and will be manipulated is not a good one. It's certainly not what you want, and this is why I'm saying the internet can be used for critical discourse, but when it comes to collective decision-making, it is very dangerous, and it's best to turn it off when it comes to voting and real decision-making.

Alessandro Oppo: I understand what you're saying. I hope that there's still some way to maybe not use the voting system anymore, but eventually to deliberate, just talking as we are doing now, about certain political issues.

Geert Lovink: Seeking consensus is of course the ideal, but I'm still very much in favor that we do more experiments. In the last decade, not many such experiments have happened. You could say okay, maybe with the DAOs and the blockchain experiments, that was an attempt in that direction. But when you start to look at it - and we've recently studied and published a study about that by Inte Gloerich, one of our researchers here at the Institute of Network Cultures - you can see that these experiments are very few and the outcome is quite mixed.

It shouldn't stop us from making further inquiries in that field, but it is quite telling that despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of humankind is using these machines and devices, very few experiments are happening in this direction.

Alessandro Oppo: We should experiment, and maybe we find something that works. I'm excited about DAOs and blockchain. I'd like to ask about the relationship between money and the political system, but also because I know about an initiative called MoneyLab.

Geert Lovink: I've been intrigued with the question of digital money from very early on. Here in Amsterdam in '92, I already met David Chaum, who is the inventor of DigiCash. Please read the Wikipedia page about Bitcoin - he is considered one of the intellectual founding fathers of Bitcoin. He was working here in Amsterdam.

The question of how people can make a living with these computer networks is completely unresolved. Most of the hackers already told me in the nineties: you will not be able to make a living with the internet, forget about it. You can maybe make a living if you're a designer or a programmer and you work on the actual infrastructure of it - there's some money to be made there. But if you are making music or writing poetry or a novel, or a journalist for that matter, forget about it. You can have a normal job and then you can do that in your free hours in the evening, because you will never get money for what you're doing.

This has been a decision of the people who have designed the systems very early on. So it was always an uphill struggle, and it still is.

Alessandro Oppo: My last question: do you have a message for all the people that are actually working in the civic tech field, experimenting with technology, building software that should help people to deliberate or to agree on certain topics?

Geert Lovink: For sure, because in my field we had to at some point confront ourselves with social media and what we call platform blues. This is something we have not done voluntarily but only to understand deeper the drive into the implementations and the premises of this right-wing libertarian populist movement that was driven and pushed forward by Silicon Valley very early on. This tendency has been around already - it was there in the mid-nineties. The right-wing techno-libertarians go back a long time, and if you read that famous essay called "The Californian Ideology" by Barbrook and Cameron from 1995, it's already all in there.

We had to confront ourselves with that movement, with that force, which now with Elon Musk and Donald Trump is kind of reaching a Hegelian world history level. It makes you wonder if it can get any bigger than where we are at the moment. Why not? Maybe it can cause World War III and the destruction of the planet as a whole. I mean, that's really the next level we're approaching sooner rather than later.

So the question is: if you have to confront yourself with that because you need to give an answer, what is then the status of small scale alternatives? People who are working on the software, protocols, and prototypes you are mentioning?

I would say that at the moment we really should come together here in Europe - in Italy, France, in Germany, Netherlands, Spain, everywhere in Eastern Europe - and come together to discuss how we in the next couple of years want to relate these activities in a completely new way.

Because if we are not opening up this discussion, we may as well follow the news of what Musk and Trump and Zuckerberg are doing every day. What we see also in Italy is that the counter-movement is more and more just confronted with keeping up with the news, because nobody can really keep up with it, but this is also taking away a lot of our energy and attention from the alternatives.

The alternatives are out there. There are a lot of people amongst us with very good ideas. We are running in the real danger that we have to focus so much of our mental energy and collective anger towards what some call the poly-crisis - because it's a poly-crisis, related to extraction, global warming, the disastrous effects of AI. The list of the poly-crisis, as we all know, is very long.

So day in and day out, we can just be completely overwhelmed just by dealing with that, and thus forgetting that we have a whole range of quite interesting alternatives that have been developed in the background by small groups, collectives, initiatives. We really need to politicize and find a new balance between these two things that ask for our attention, and that's really the challenge ahead for the next couple of years.

Alessandro Oppo: Thank you a lot, Geert. Very, very interesting for me. Greetings to Bologna.

Geert Lovink: Thank you. Ciao.